INTRODUCTION

How does the learning and employment ecosystem (hereafter called the Ecosystem) work? What are its problems? How can we address the Ecosystem problems related to the higher education system and make it more efficient and effective?

In the post-war boom era of 1950, less than 15% of the US population completed four years of college to earn a credential. In that period a degree, by itself, distinguished the learner/earner from more than three-quarters of US workers and so a degree

carried inherent value. Today, about 38% of the population in the U.S. have completed four years of college. The job market followed this trend: Per the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce, in 1973,

28% of jobs required post-secondary education, but in 2018, 63% of jobs offered required some post-secondary work. Ironically, 33% or more of all college graduates are working in jobs that don’t require a college degree. At the same time, higher

education is going through a period of increased scrutiny and accountability regarding the return on investment (ROI) of their credentials and how well they serve recipients.

In addition, the cost of a college degree has risen dramatically over the last 20 years. “Between 1980 and 2020, the average price of tuition, fees, and room and board for an undergraduate degree increased 169%”.

There appears to be a disconnect. The workforce is demanding more post-secondary attainment and skills more directly related to employer needs, yet many learners who have earned the expensive credential cannot find employment or a position commensurate

with their degree. This has placed public scrutiny on the value and return on post-secondary investment.

In 2018, Harvard Business School Professor Clayton Christensen predicted that 50% of colleges and universities will close or go bankrupt in the next decade. The fear is that as they are currently funded and managed, colleges may increasingly be unable

to cover their costs through revenue. There is increasing competition from accredited, non-traditional colleges such as Western Governors University (in business since 1997, with over 120,000 current students) and Southern New Hampshire University

(a formerly traditional college which became a non-traditional university in 2001, with currently over 130,000 online students), from alternative education entities such as boot-camps like General Assembly, from online course providers such as Coursera

and Udemy and from corporate training organizations.

It seems there may be alignment issues between providers of learning and fulfillment in the employment economy that go beyond the last few years of COVID.

So, to restate this issue, how does the learning and employment ecosystem work? What are its problems? How can we address the Ecosystem problems related to the higher education system and make it more efficient and effective for the learner?

WHAT IS THE LEARNING AND EMPLOYMENT ECOSYSTEM?

The learning and employment ecosystem is the set of stakeholders, organizations, policies and practices (including laws), tools and data that collectively interact to enable learning, learning attestations (credentials), hiring and the pursuit of careers.

Overview of the Ecosystem

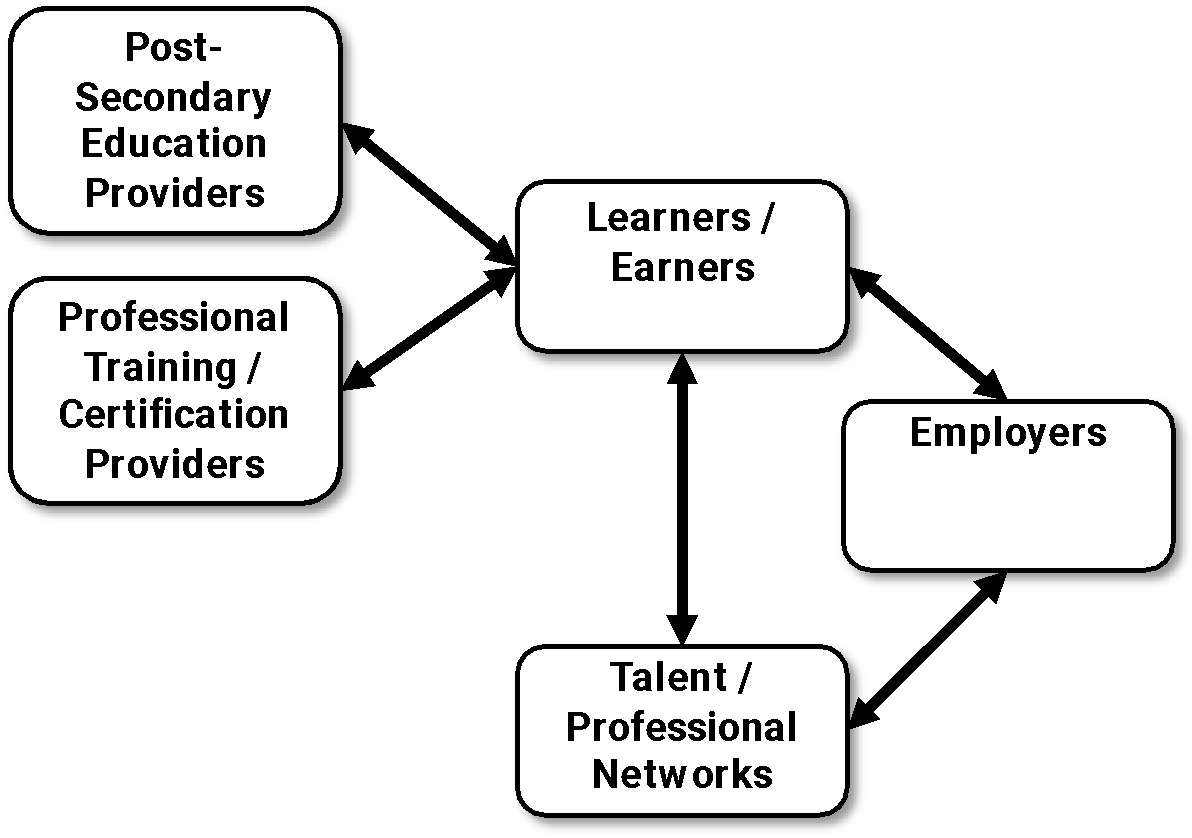

The following is a very high level of the Ecosystem and its key stakeholders:

Figure 1

The arrows in this diagram represent the primary engagements between the key stakeholders.

Learners/earners clearly engage with education, training, and certification providers and, separately, with employers and with talent/professional networks (e.g., Indeed or LinkedIn). Employers also use those networks to search for potential hires.

Though there are opportunities and occasions where education providers may engage with employers or talent networks, those tend to occur on an individual basis and not as a standard Ecosystem function.

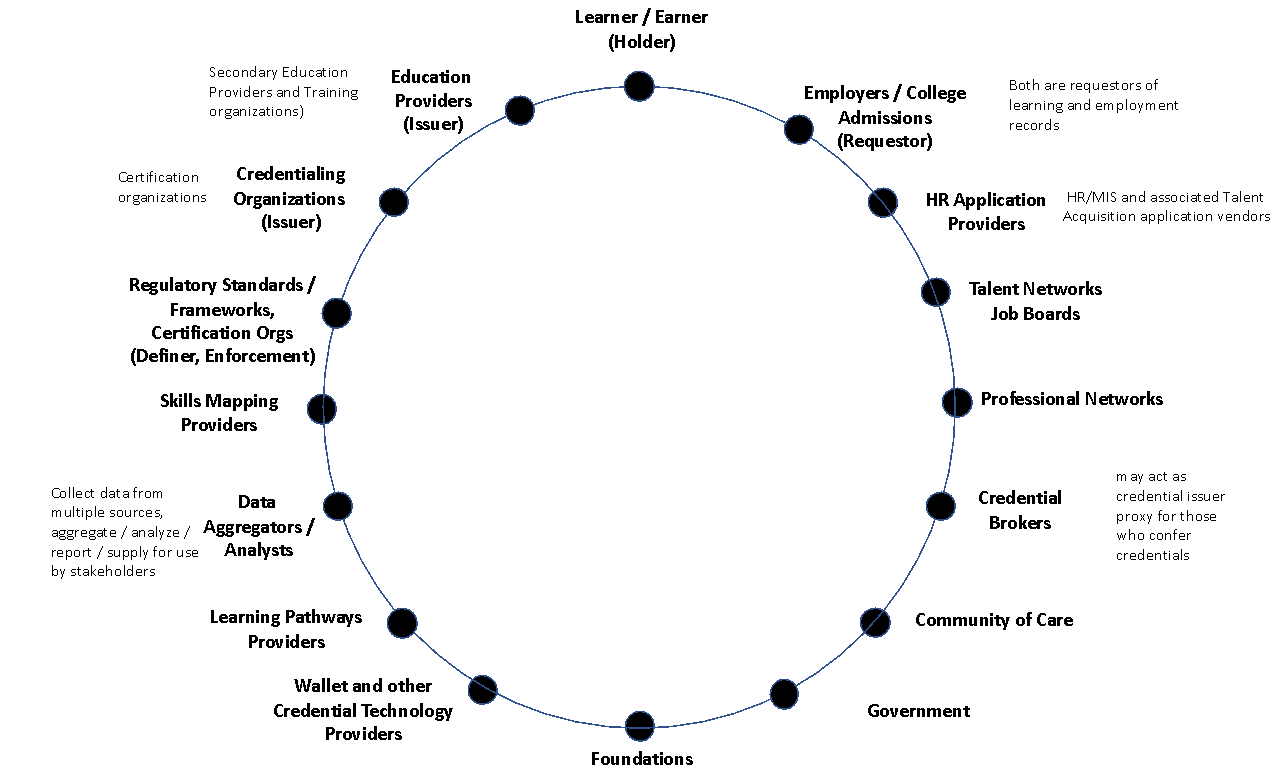

The Ecosystem actually includes many stakeholders and many, more complex relationships.

Figure 2

The great variety of stakeholders (depicted above) have various relationships with each other. For example, credentialing organizations such as state nursing boards, define standards that graduating nurses must meet and provide testing and related

management of their certifications, which are in turn, used as evidence of credentials for hiring by employers.

EVOLUTION OF THE ECOSYSTEM FROM THE PAST

The Ecosystem has evolved organically and in an ad hoc fashion. Around the turn of the 20th century, there were no automated means of managing staff or students, no electronic networked communities of professionals, and almost no standard means of

describing learner/earner achievements. In those days, the most common means of hiring was to post jobs in a newspaper or place signs on the factory door. The most common means of assessing a job candidate was either their references (who may

have been friends that were current workers in the company) and in a very small number of cases, college degrees. Once hired, a period of apprenticeship often served as the primary mode of professional training for the employee to acquire the

necessary skills for success in the position.

As the job economy evolved, job needs became more differentiated. For example, a factory worker before the 20th century may have needed to bring few skills to the job, as evidenced by the use of child labor in the past. Today, many factory workers

have very specialized skills, including training on specific manufacturing processes, safety, numerical control machinery, and perhaps even specialized training in chemistry or biology. Since the late 20th century, a determination of competency

was often based on the assumptions that 1) a degree provided the foundational set of professional competencies and skills and that 2) a candidate with a post-secondary training could master the more specialized requirements associated with a specific

workplace or industry. The candidate may also be required to have certifications and maintain ongoing training to keep up with changes in the manufacturing processes and technology.

This evolving differentiation of specialization within existing jobs and the creation of novel new jobs (sometimes in waves, in areas such as electronics, aerospace and today in biological sciences, medicine, and technology) have outpaced the scope

of many traditional college degrees. Today, it may not be enough to have a degree in an industry in need. One must have specialized skills and the skills are sometimes becoming as important as the degree. Note the rise in jobs that do not require

degrees (such as programming and user interface design).

Leading companies recognize this skills gap. IBM employs over 250,000 employees and has a very large number of jobs posted. Over 50% of those jobs require skills and competencies but do not require degrees.

This shift to skills-based hiring can actually have benefits to many in underserved communities in the USA. In 2019, over 40% of white Americans had a college degree, while only about 26% of Blacks and about 19% of Hispanics had a degree. In a world

where the attainment of skills can secure jobs, and a world where the cost of attaining skills is lower than the cost of a college degree, underserved communities may be able to achieve greater equity in hiring.

CURRENT STATUS OF THE LEARNING AND EMPLOYMENT ECOSYSTEM

Over the last 75 years, organizations have used shared policy, technology, and automation to improve many aspects of the Ecosystem. Today, there are a number of automated means to capture, analyze and provide student information, employer staff information,

and various means for employers and job seekers to connect through the internet.

Higher education programs have evolved to include training on newer technologies and a number of accredited institutions offer non-degree training for employer needed skills that do not fall in the more traditional programs.

However, these improvements have not kept pace with the fast-evolving job economy.

Proprietary automation systems fail to use open data standards

Per the Open Data Institution, open standards for data “...are documented, reusable agreements that help people and organizations to publish, access, share and use better quality data”. The use of open data standards enables various players

within a business space to work together to provide services such as the telecommunication or banking industries. Successful implementation of open standard adoption balances the need for technical innovation by adopters and at the same time minimizes

incentives for proprietary solutions that threaten interoperability. However, today, many medium to large US employers typically use one of only a few HR/MIS systems to manage their staff information. Each of these systems maintains data in proprietary

forms that is not “digitally readable” by other systems and is held in centralized data repositories. Even the cloud- based offerings typically have a virtually central repository, managed by the vendor.

The same is true for student information systems used by higher education entities. The paucity of data interoperability in these areas is particularly striking. There were open data standards describing and exchanging education records propagated

as early as 1990 (e.g., post-secondary transcripts via SPEEDE EDI) and the Open Badges specification first appeared in 2012. Yet, fewer than 20% of the US Higher Education schools

use the PESC SPEEDE transcript standard and none of the major HR/MIS vendors or SIS vendors provides native support for learner/earner badge or CLR data using any of these standards.

Semantic Interoperability

Most employers/industries do not describe jobs or employee achievements in skills-based language. Only a few employers (e.g. IBM, AT&T), have standard skills-based means of describing jobs or employee achievements, even across their own internal

departments.

In some exceptional cases, organizations have collaborated to provide skills-frameworks (a model for defining the skill and knowledge requirements of a position..) to inform job descriptions and training. Two notable exceptions are the NIST NICE framework

for Cybersecurity and the PMI PMBOK framework for project management.

Many years ago, industry determined the need for rigorous skills in project management and collaborated to define the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK), which is still collaboratively maintained today, facilitated by the Project Management

Institute (PMI). This skills framework is extremely detailed and rigorous. It is managed by a collaborative group of industry experts and there is training provided by various organizations to assure trusted certifications that meet the standards.

In every industry which uses project managers (PM), these project management certifications are trusted and used as evidence of competency, relieving the hiring managers from having to individually (and perhaps idiosyncratically) define the needed

job skills.

More recently, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) convened experts from industry, government, research and education to jointly define the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education (NICE) framework. This framework describes

“the tasks, knowledge, and skills that are needed to perform cybersecurity work performed by individuals and teams”. The efforts have also extended to education. The NICCS Education and Training Catalog now includes a total of over

6,000 various NICE aligned courses offered through hundreds education entities.

However, these excellent examples are in the minority.

Some HR/MIS vendors (e.g. Workday) and talent networks (e.g. Eightfold) have provided skills “clouds” for their (employer and talent) clients, allowing clients to choose from partially curated skills terms. However, even when derived from

industry sources, these are not industry vetted or collaboratively maintained and typically do not include descriptive information, only key words.

A number of employers and industry organization make reference to O*NET, a free, online, government supported “Occupational Information Network” which does have hundreds of job definitions. However, this promising data source is not used

rigorously by industry or education and tends to be a retrospective view of the US job market rather than a frequently updated snapshot of collaboration among industry, education, and government on current and projected needs. For example, Cloud

Computing, Agile Coach and Scrum Master are well known job functions in information technology and likely considered to be mainstream today (not new, leading-edge jobs) as well being listed as “jobs of tomorrow” in a 2020 document

by the World Economic Forum, but they are not listed in O*NET.

Similarly, there are commercial companies which provide market data concerning jobs, however, many are proprietary and only offer access by individual entities through a fee.

Many traditional education providers typically do not describe curriculum or degrees in terms of skills, and when they do, it is done within a limited number of disciplines that more easily accommodate the practice (e.g. nursing, STEM).

The more volatile the industry the more likely that skills-based learning will be preferred over traditional degrees. In the past, A computer science diploma sufficed to assure a career in technology related fields. In more recent years, a more specialized

degree was required for this assurance. Now, even a specialization may not assure a job, as computer technologies evolve quickly and require constant learning.

The traditional mission of large (R1) public post-secondary education institutions is threefold: the transfer of knowledge (instruction), the generation of new knowledge (research) and service to the institution and the public good. The instructional

mission concentrated on the delivery and student mastery of material associated with the disciplines comprising the schools and defined by the curriculum. These disciplinary learning outcomes were the deliverable but may or may not have been

recorded by the institution in a systematic manner. In some cases (e.g., the STEM disciplines) these learning outcomes were directly applicable with the skills and competencies required to be successful in both the workplace and the academic

arenas. However, in others (e.g., the Liberal Arts and/or Humanities disciplines) learning outcomes could not be easily mapped to labor market skills. However, implicitly, it was previously assumed that degree attainment served as a signal

that labor market skills were mastered.

Traditional education entities are often constrained by governance and business models built to serve these missions. These practices give great freedom to individual, tenured professors and lean toward more conservative approaches supporting

the traditional disciplinary curriculum and the pedagogies delivering them. These processes were also defined to help preserve accreditation. However, this model does not immediately lend itself to revise curriculum to include skills-based

learning courses, particularly skills that are not explicitly aligned with the subject matter (e.g. critical thinking, analysis, leadership, group engagement). In turn, this makes it difficult to express broad credentials such as a bachelor’s

degree in terms of skills and competencies. Note that institutions with central course design or curriculum control (most often community colleges) are not as constrained by the model described here.

Recently, it is becoming more common for higher education institutions to express and record learning outcomes in a more systematic fashion. In part, this is because accreditation bodies have begun to cite the need for more detailed outcomes as

part of their review and in their findings. As a result, disciplinary learning outcomes are beginning to emerge as a more common element within a system of record, or at least as managed information for the learning enterprise. In the more

forward-looking institutions, learning that occurred outside the classroom is also being managed, recorded, and expressed on behalf of the student. The combination of greater emphasis on recording learning outcomes and recognizing learning

where it occurs has been led by some institutions who see value in mapping their curriculum to skills. For example, Western Governors University, Southern New Hampshire University, University of Maryland Global Campus have adopted curriculums

embracing this approach. There are also more traditional institutions that have highlighted learning outcomes and student achievements at a more granular level such as Temple University, Stanford University and Johns Hopkins University.

WHY SHOULD HIGHER EDUCATION SUPPORT THE EVOLUTION OF THE ECOSYSTEM?

When higher education and industry align on skills, everyone wins. Learners achieve and demonstrate industry needed skills, educators promote the value of their “brand” and back it with marketable outcomes (graduations, hires),

and employers hire better qualified employees and retain them longer. All stakeholders collaborate to create a virtuous cycle of improvement.

Service to the Learner

In a world where the credential issuing organization aligns skills / competencies to the credential, the learner is able to provide trusted (not self-) assertions of those skills. Without the issuing organization anchor of trust, both the

learner and potential employer must make assumptions about the relationship of the skills to the credentials, and this leaves room for bias and interpretation.

In the current Ecosystem, it is critical for job candidates to be able to articulate the specific skills and competencies requested by the employer. It is the only way to differentiate themselves and their higher-level achievements (e.g. degrees)

from others competing for the same job. Providing their learners with an organized set of learning outcomes, skills and competencies associated with their program and their learning activities (e.g., courses, internships, research activities,

etc.), arms them with a focused summary of their achievements and better prepares them for engagement with employers.

Students with well-defined skills and competencies are also less likely to be subject to equity issues in hiring. Hiring based on achieved skills helps limit the institutional reputation effect of selecting only candidates from well known

schools on the assumption they are better qualified. In addition, skills-based hiring helps overcome the perceived lack of ROI of education by demonstrating the valuable skills achieved by students who have graduated from less expensive

schools.

Over a third of college undergraduates change majors. Over 61% of graduates would change their majors if they could go back. The education institution might be much more effective in helping students by using skill based learning to help guide

students in achieving their aspirational goal (workforce or advanced degree). Skill learning can particularly improve student counseling (with appropriate assessment and feedback models) for students in mid-course by demonstrating adjacency

in skills already achieved through prior learning.

Service to the Institution

Assigning and aligning skills / competencies to courses and degrees can competitively differentiate the institution. As discussed above, employers are looking for personnel with specific skills, even if the employers vary greatly in how they

describe those skills and have yet to adopt a systemic approach. Having higher education credentials that map to skills provide alumni an advantage with employers and thereby enhances the institution’s placement, recognition and

reputation.

This also provides the institution with the ability to more closely collaborate with employers, which can result in employer funding of institution initiatives, internships for students, and the potential for non-traditional post-degree education

program offerings by the institution, designed for employees and paid for by employers.

To assist learners in their ability to assert their credentials, AACRAO is leading the movement to improve Learning Mobility. Improving learning mobility supports the learner’s institutional journey into and through

post-secondary higher education into employment and lifelong learning. It is at the center of the work of the association’s members. Framing the whole of the work under one umbrella highlights the whole of ecosystem and lays bare

the opportunities for improvement. We see learning mobility as a Learner-Centered innovation, where systems, processes, programs, and initiatives must be designed around the needs and best interests of the learner of today

and the future at every stage of their journey. All of our projects in this space embrace central themes and drivers:

AACRAO is working both nationally and internationally to increase Equitable Outcomes - All systems, processes, programs, and initiatives must enable educational, social, and economic mobility for people with varying

abilities, preparation, and skills. This supports pathways to better employment opportunities and to further education and training.

This necessitates a commitment to Interoperability & Open Standards - All technology must use open standards and common ontologies/frameworks to enable data to be machine-readable, exchangeable, and actionable

across technology systems and, when appropriate, on the Web. It must support combinations of data from multiple sources, enable human interoperability, and be understood by people in different occupations and industries from diverse

backgrounds.

When we do this well, we Strengthen the Value of Higher Education - In a knowledge-based economy where being highly skilled and experienced is valuable currency for success and economic growth, education serves as

an accelerant to credential attainment. Documenting and communicating that attainment is an imperative and AACRAO members are critical to this work.

Since 1910, AACRAO has been at the forefront of managing and documenting learning - with registrars documenting learning and issuing its artifacts and admissions operations evaluating said artifacts.

Using skills/competencies based mapping to courses can greatly simplify the transfer and articulation process for an institution, providing incentives and assisting in creating timely credential pathways for students to transfer to the institution.

Higher ed credentials that carried both disciplinary and professional learning outcomes, course descriptions and additional information that would ease the task of placing the student’s course history into the accepting institutions

curricular context. This approach can reduce effort and costs for the institution and also lead to greater student retention, since the students can directly see the marketable skills value of their achievements and they can be more easily

and correctly inserted into the institution’s academic program.

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO GET STARTED?

Evolving education institutions to better support the skills-based Ecosystem benefits all key stakeholders. Institutions do not have to “eat the whole elephant” to get started.

Some recommended approaches are:

Identify programs/departments that serve in-demand jobs and work with instructors, administrative support and/or consultants to generate learning outcome/skills-based descriptions for their courses. These do not necessarily require

the instructor to rewrite course descriptions but allows the institution to correlate or enhance those descriptions with the skills/competency information.

Identify courses and/or experiential learning activities that lead to student attainment of a specific award (e.g., certificates) including the expressions of the skills and competencies the student demonstrated to earn the award.

Examples include undergraduate research, internships, supervised community support programs and others.

Capture the skills/competency information for the courses within the course management system (whether it is part of the SIS or in another system). This may be done by either using existing system data fields or creating an associated

table. If a table is created, it should use (or can be converted to) the Open Badge (OB) or the Comprehensive Learner Record (CLR) standard data structure. Committing to these standards means the institution can interoperate with others who issue and receive digital credentials. This will directly

benefit the learner and provide for more cost-effective record processing for the institution.

Provide a means to generate an enhanced student report or transcript, preferably following the OB or CLR standard, that captures both the traditional student transcript content and the underlying achieved skills/competency information

in a machine-readable form. If the information was already captured in this form (see #3) then it becomes extremely easy to report it out. In either case, using these standards can make that relatively easy and can become an automated

process for any skills/competencies-aligned courses.

Create a policy (or policies), and the practices supporting it, to guide the institution toward its digital credential vision. In much the same way that policies define currently issued credentials, digital credentials or skills-based

policies should specify what is issued and distinguish it from traditional ones. This exercise need not be onerous. Rather, it should be similar to traditional policies and assist all in understanding the credentials being asserted.

This is a minimal effort that can be scoped as narrowly as a few courses in a single discipline or more broadly, depending on the institution's resources.

In following these steps, first in a small way (e.g. perhaps single program or department and perhaps only undergraduate courses in the major), the institution now has tools to

Help market the value of the program to potential and current students

Help students with learning and career pathway counseling (by reference to needed job skills)

Work with employers to perform early placement (internships) and promote the institution brand

Collaborate with employers to align the descriptions with the industry skills needs

Demonstrate positive outcomes in terms of retention and hiring, again promoting the brand

Then the institution can expand to include more courses, programs, and work more closely with industry, government and others to achieve a better alignment of skills and competencies for mutual gain. .

At some point, the institution will likely want to address related technologies and services with regard to skills and competencies. These may include:

The institution issuing trusted “badges” or microcredentials for achievements, using the Open Badges standard.

The ability to award “stackable” achievements as “badges” or microcredentials for skill attainment within components of a course and groups of courses, such that someone who completes a course, not only gets

course credit but multiple microcredentials for well-defined skills achievements, and those who do not finish a course may still achieve partial credit for the attainment of some of the defined competencies in the course.

The promotion and governance of co-curricular activities to the status of credentialed skills / competency achievements by the institution.

The use of an institution or institution affiliated “wallet” (a digital wallet is an app or online service used to store electronic documents) .for students and alumni to maintain their achievements in a form that is digitally

readable in a manner that the wallet owner has control over with whom they share their information.

The ability to aggregate credentials and related achievements from multiple sources (other education institutions, certification entities, employers) such that it represents the “whole” learner / earner (this is often referenced

as a Learner and Employment Record (LER)). This in turn can be a means for the institution to engage (with the wallet holder’s permission) in meaningful additional learning and alumni opportunities.

Building on the skills / competencies aligned curriculum, the use of technologies to support the institution and learner provides the institution with greater influence with all other stakeholders in the Ecosystem and creates viable additional

revenue opportunities.

WHAT IS IMPEDING THE EDUCATION INSTITUTION FROM THIS NEXT STEP?

Some education institutions already utilize skills / competency-based curriculum. Some already work collaboratively with competency framework organizations to align their credentials. Some already collaborate with industry employers to align

with employer skills-based job descriptions. A few also offer digital wallets or other means to aggregate credentials from multiple sources. However, these typically represent the few, most innovative institutions.

With the current scrutiny on higher education return on investment and the issues in the job market, why haven’t more education institutions moved toward a standards-based, skills / competency aligned, digitally readable approach?

Challenges to the status quo

As mentioned above, most traditional higher education institutions continue to use decades old governance structures, business models and policies that militate against change. On the one hand, these institutions rightfully want to align with

their traditional missions. On the other hand, for some traditional institutions that legacy is quickly becoming less valuable in a world of skills-based hiring. The new motto is “why learn when you can earn?”

If we accept even a milder version of Clayton Christensen’s prediction, this inertia will ultimately eliminate those education institutions that are less willing to change, less willing to prove clear value in a skills-based economy.

Those who fail to make this transition may not survive. In chapter one of what is today a canonical book on the way information transforms strategy, Evans and Wurster write about the debacle of Encyclopedia Britannica, long the standard for

comprehensive information. The advent of Encarta, a cheap or free digital encyclopedia, with multimedia, available on a CD, caused the traditional paper book-based encyclopedia market to be “blown to bits” and Brittanica could

not compete. Even when Brittanica later attempted to create their own digital version, they were not competitive in the market. The moral is that you must embrace the evolution in information and technology to survive and that you must

get ahead of the wave or drown.

Perceived ROI issues

Complete adoption, implementation, and maintenance of skills / competency-based alignments to courses and degrees (and the rubrics and assessments to support them) will require some initial and some ongoing work. There must be a reasonably

demonstrable return on the investments required to make such changes.

In addition, the investment is not likely to show financial value for several years, until improved outcomes in areas such as student satisfaction, retention, advising, transfers and transfer administration, and graduating student successful

hiring figures can be collected and demonstrated.

That is why the recommendations above suggest starting small and in places that can prove value in outcomes.

The good news is that institutions don’t have to “eat the whole elephant” to evolve toward skills-aligned programs and that there are organizations, consultants and tools that can help this effort in a cost effective

and efficient manner.

Technical Challenges

The greatest service that education institutions can perform would be to press their administrative software providers (e.g. student information system, learning management system and similar) to adopt the Comprehensive Learner Record,Open

Badges and related standards for maintaining learner data and achievements. If the vendors supported these standards, then the individual education institutions would not have to consider the cost of additional development to adapt

these products to the standards. There would be much greater interoperability among these products and other (e.g. employer) systems as well, which would simplify institution IT efforts and lower costs.

In lieu of this, institutions need to create and maintain data in these formats (or provide for their conversion) and that will require some development work (though this might be shared among institutions that use the same vendor software).

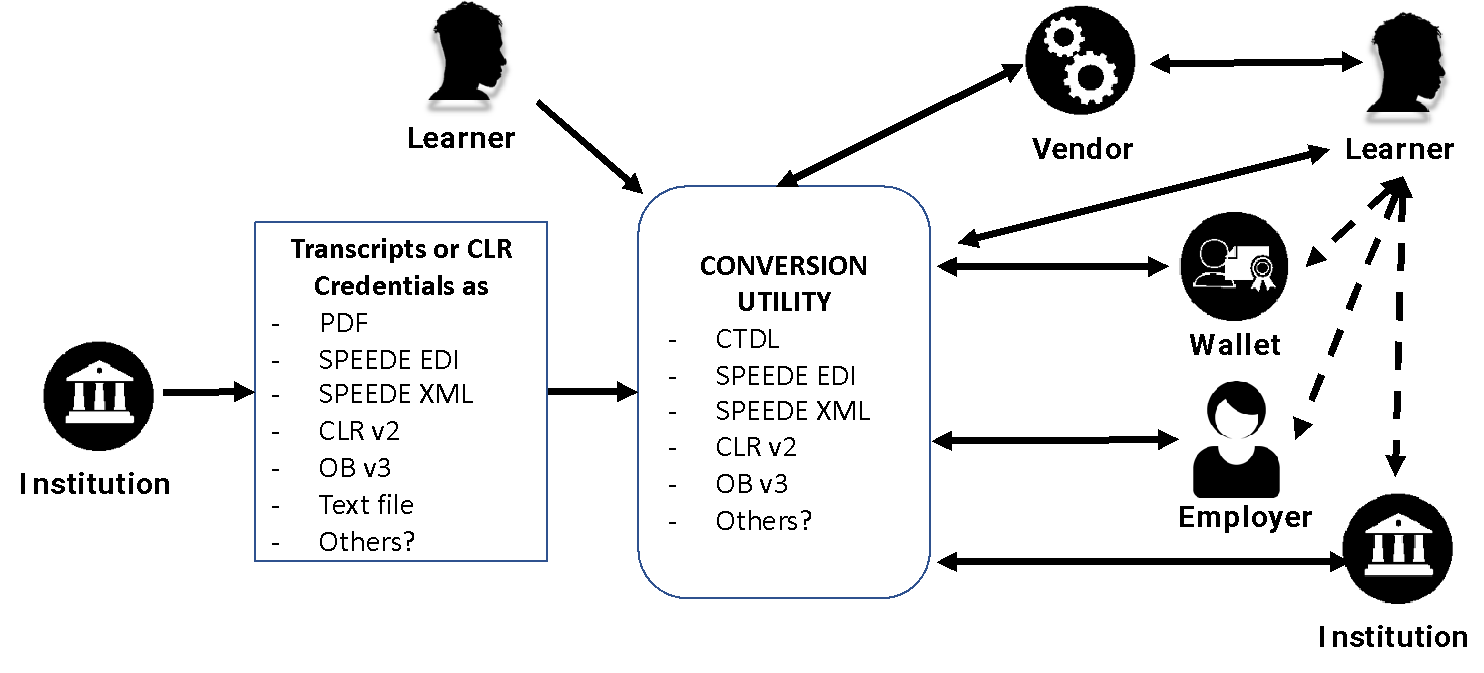

There is also current discussion about a consortium based approach where credential issuers transmit their information in a manner that best suits them (e.g., text based format(s), transcripts formats, PDFs, ) to a conversion engine

that will transform the data received into one of the accepted data standards.

Similarly, as institutions commit to issuing digital credentials and digital wallets, there will be some investment to support these technologies. Luckily, the industry appears to be moving toward low-cost models and open-source technologies

for these efforts and this should minimize the technical effort for institutions.

Legal and Policy Issues

The education institution is responsible for a “system of record” for the learner. This means the education institution conferring the achievement to the learner acts as the trust anchor for the truth and integrity of that

information.

With GDPR (the European General Data Protection Regulation now in widespread use around the world), FERPA (the US Family Rights and Privacy Act), FCRA (the US Fair Credit Reporting Act) and other similar regulations, the roles, and responsibilities

of those who issue credentials, those who possess them, those who may make use of them and those who request them are legally constrained.

These issues do not directly affect a move to skills / competencies aligned curriculum but do affect how credentials are digitally issued and managed by each of the stakeholders.

Therefore, we must distinguish the more straightforward move to aligned curriculum from the more legally constrained creation and use of learner / earner specific data. This topic is not new to education entities, who already have controls

in place for managing protected student data and how students access and share that data. The additional incremental effort for supporting the legal aspects of creating, maintaining, and sharing digitally readable credentials remains.

As an issuer of a credential, the education institution understands the creation and maintenance of the system of records and any derivative representations. If the education institution determines to provide or license a wallet for their

students and alumni, they will need to assure that they understand the legal responsibilities in managing the wallet. There are a number of wallet providers (more each year) who provide solutions that may address these needs, but they

will need to be vetted and contractually obligated to meet the legal requirements.

Once the information is legally received, employers typically own responsibility for how they use personal data provided to them by the wallet holder. This is typically not a responsibility for the credential issuer.

Financial Incentives and Disincentives

One of the barriers to adoption of a digitally readable and learner self-sovereign set of credentials is the potential loss of fee revenue for the issuing education institution. At a large number of institutions, the costs of operation

of the Registrar and related offices are offset, in whole or in part, by charging for the generation and distribution of transcripts. In a world where the digitally readable content of a transcript and its credentials (courses, degrees)

are in a wallet, in the control of the wallet holder (learner self-sovereignty), these fees are at risk.

Various business models can mitigate this problem and provide a viable means to manage and preserve the revenue for education institutions. These include:

A modest increase in annual (or periodic) student fees.

A document or credential fee levied at student matriculation or on a per enrollment (semester/quarter) basis.

A per use or subscription charge to employers for the verification of an education entity credential. This allows the employer to request the credential and allows the wallet holder to allow the employer to see the credential but

requires the employer to pay a fee to the issuing organization to see the verified credential. This requires that the wallet or the underlying platform support the accounting and charging for this effort but provides a direct

correlation to the current transcript charging practices and can establish a steadier form of revenue to education institutions.

Note that the ability of the institution to provide direct verification to an employer can relieve the employer from needing the intervention of third party credential verification services, a strong benefit to employers and a clear value

to the issuing organizations who get fees for services and data which they manage.

A charge for issuing credentials to a wallet. This is considered a less viable approach, as it likely puts the burden of the cost directly on the wallet holder and therefore creates a disincentive to use the wallet.

Each of these options offer promise and there may be others to explore. Each option requires further investigation to determine any other issues or problematic circumstances that may inhibit their adoption. However, the movement toward

learner self-sovereignty is gaining momentum and should be addressed. As stated above, this is independent of the skills-based credential definitions, which support both a traditional and self-sovereign model.

WHO ELSE IS DOING THIS NOW AND WHY?

The following are several institutions, employers, and geographic areas already pursuing this path and their reasons.

Western Governors University has been a higher education pioneer in competency-based education that is job relevant. WGU is an accredited university that has also managed to orient their course and achievement offerings as competency units.

Their courses map to competencies and they have been the leading organization facilitating the Open Skills Network, a “coalition of employers, education providers, policy makers, military, non-profits, and other stakeholders

dedicated to advancing skills-based education and hiring.” WGU can be considered a model for other higher education organizations looking to provide skills / competency framework mappings for their education offerings.

IBM has dedicated its efforts to hiring based on skills-first. Even by 2020, 43% of IBM’s open job requisitions did not require a traditional diploma. IBM also offers training and badges (using Open Badges) for both its own employees

and public learners, including many free courses.

Arizona State University has augmented their traditional credit hour based traditional programs’ and credentials by offering microcredentials representing demonstrated learner skills or competencies. They have a mature governance

process surrounding the administration and issuance of their credentials and have developed a digital wallet platform (“Pocket”) to combine their learner’s verifiable traditional and digital credentials. The wallet

also enables the learner to curate and assemble a portfolio of these verified credentials germane to the opportunity (e.g., employment) they wish to pursue.

As discussed above, more traditional institutions are finding ways to express more information about the learning that occurs in and out of their classrooms. Stanford University has begun issuing digital credentials for their online programs,

Temple University is issuing a version of a Comprehensive Learner Record that includes course descriptions and learning outcomes for their course and programs and Alamo Community College has implemented a well defined digital credentials

program. Though widespread adoption of issuing digital credentials expressing detailed learning outcomes and skills for the benefit of their students is relatively new, there does appear significant interest and traction in the space.

CONCLUSIONS

The job market is in crisis. The education system supporting the Ecosystem is under scrutiny and in crisis. In the job market, we see waves of layoffs simultaneous with hiring practices that result in equity issues and poor alignment

between the candidate skills / interests and the job. Job dissatisfaction creates high employee turnover. In 2022, the overall cost of voluntary employee turnover amounted to over $1 trillion.

In response, employers are moving toward skills-based hiring and job candidates are moving away from traditional degree programs. The economy is rallying toward this approach.

Citizens entering the job market are strongly questioning the cost / value of a degree and the sense in postponing entry to the job market.

It is in the interest of higher education to consider these issues, become active in the Ecosystem and to support their student learners' future career opportunities.

One solution is to align curriculum to the needed skills, collaborate with employers to ensure alignment with the jobs and to make the issuing of credentials efficient and standard. There may be an advantage for those Institutions

that adopt this approach.

What’s Next?

How can education institutions overcome their impediments to change and become more competitive?

Start small – start with skills / competencies alignment to a well-defined curriculum for in-demand jobs in industries that may already have some skills frameworks. These might include cybersecurity, project management,

health care (e.g. nursing), veterinary, and other similar fields.

Enhance the institution’s systems (SIS, LMS) to support skills-based information using standards based formats.

Collaborate with employers to define skills and align curriculum and job descriptions, especially those that reside in their community and whose industries are supported by the institution programs.

Build/define operating policies and practices encompassing the issuance of digital credentials.

Work to evolve the institution business model to become less dependent on transcript revenue and more focused on transactional verification of credentials by requestors

Pilot wallets and digital credentials, perhaps in non-degree offerings first and determine the best approach for the institution.